A WATERY LANDSCAPE

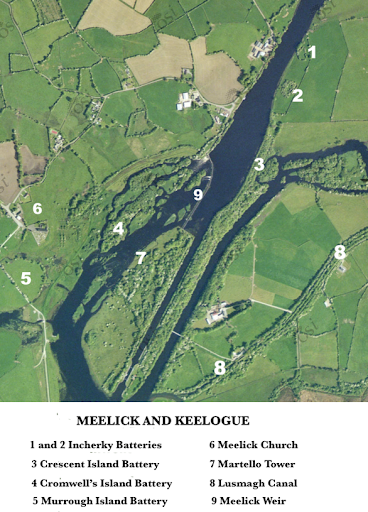

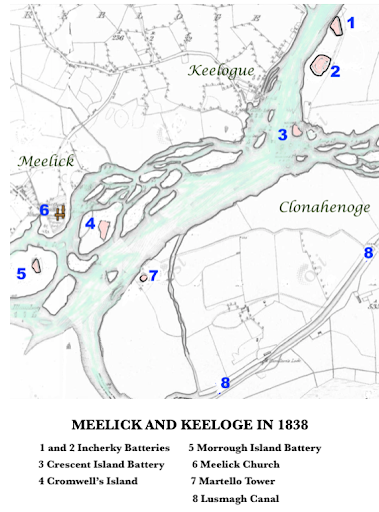

The aerial photograph and historic map above may help to familiarize readers with the watery landscape which provides the setting for this presentation. Both show the River Shannon as it flows between the parish of Lusmagh, in the west of County Offaly and Keelogue and Meelick, in the extreme east of County Galway. The area is about six kilometres downstream from Banagher. The map is based on the first edition of the Ordnance Survey 1838 and the photograph was taken in recent years. Comparison of the two images will show how the building of Meelick Weir and Victoria Lock between 1841 and 1844, and the creation of additional channels and embankments allied with the removal of islands, mill races and eel-weirs completely transformed the riverscape.

RECONNECTING OUR HERITAGE

It is not an exaggeration to say that the adjacent fords on the River Shannon at Keelogue and Meelick, a few miles south of Banagher, are the most historic along that ancient waterway. The Keelogue ford, was in particular readily accessible both from the high ground of Incherky Island on the east side and the uplands of Keelogue on the west. The place today abounds in historical sites and a plethora of archaeological finds discovered there are stored, mostly unseen, in repositories in Dublin, London and elsewhere. Following damage done during the high winter floods of 2009 Meelick Weir was closed to the public. The recent restoration of the weir and opening of the magnificent pedestrian bridge (in September 2021) across the Shannon has reconnected many of these important heritage sites.

THE ORIGINS OF MARTELLO TOWERS

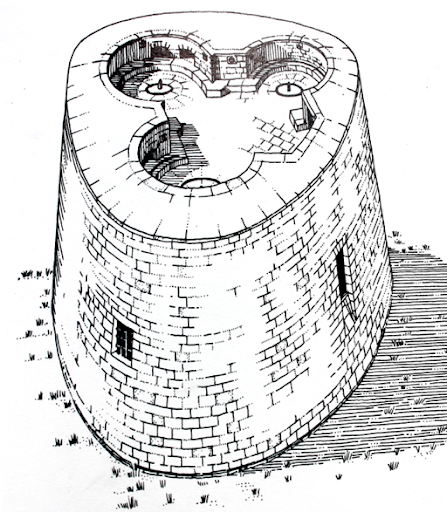

In February 1794 the Royal Navy sailed into the Gulf of San Fiorenzo in Northern Corsica and attacked a tower at Cape Mortella. The tower was eventually captured but with great difficulty and during the subsequent occupation careful measurements were taken, elevations and plans drawn and details of the guns, gun platforms, chimney, furnace and bellows for hot shots, were noted. In time the tower at Mortella became the prototype for hundreds of towers built by the British and others to ward off invading forces. These were constructed mostly in Britain and Ireland but also around the Mediterranean, Australia, Africa, North America and Canada. The word mortella means myrtle, a shrub which grew profusely in Cape Fiorenzo. In the subsequent anglicization of the word a vowel shift rendered the word as Martello.

NAPOLEONIC FORTIFICATIONS ON THE MID-SHANNON

In Ireland Martello Towers and other Napoleonic fortifications were mostly situated on the coast. Twenty-eight towers were built between Balbriggan and Bray defending the coast of County Dublin. Others were built in Wexford, Cork Harbour and Galway Bay and great batteries were built along the Shannon Estuary. So how did it transpire that the only two inland Martello Towers in Ireland were built in the heart of the country, one at Fanesker, in County Galway, just west of Banagher Bridge and the other at Clonahenoge, in Lusmagh, County Offaly, defending the ford of Meelick?

Towards the end of the eighteenth century there was a growing fear in Britain and Ireland of a French invasion. In 1796 due to the efforts of Wolfe Tone a French expeditionary force with 14,000 troops reached Bantry Bay only to be thwarted by a fierce storm which prevented a landing and sank many ships. Two years later a much smaller invading force landed in Mayo and advanced towards Dublin before being halted at Ballinamuck in County Longford. These narrow escapes alarmed the authorities and soon a network of defences was built to defend the Irish coast against attack. These were located mostly on the east and south coasts particularly around Dublin. The west coast however was much more exposed and there were fears that a landing there could not be prevented. The River Shannon was then deemed to be the landward fall-back line and defences were to be built at the major crossings along the Middle Shannon between Lough Ree and Lough Derg. Hence between 1803 and 1815 fortifications were erected at Athlone, Shannonbridge, Banagher, Keelogue and Meelick.

PHASE ONE 1803-05

During phase one, 1803-05, existing strongholds were strengthened and new temporary earthworks hastily erected. At Banagher the Bridge Barracks was strengthened to accommodate three 12-pounder cannon and downstream a temporary earthwork battery, known as Fort Eliza, was built and fitted out with three 18-pounder guns. Also in Banagher on the west bank, in County Galway, Cromwell’s Castle, a fortification of much earlier origin, was remodelled to house two 12-pounder guns. The total cost of these establishments was £1,470 6 8.

Downstream at Keelogue and Meelick fords five temporary earthworks were constructed, two on Incherky Island, one each on Crescent Island, Cromwell’s Island and Murrough Island. These works which cost £2,999 had a total firing power of sixteen 12-pounder guns and four 8-inch howitzers. Howitzers were short pieces of ordnance which fired at higher angles but lower velocity than a fixed cannon.

PHASE TWO 1812-15

Following a renewal of Anglo-French hostilities ten years later the defences were further consolidated. At Banagher seven guns then safeguarded the east bank including four 24-pounders in Fort Eliza which was then turned into a permanent fortress with the addition of extensive stonework, a magazine and a guardhouse. Fort Eliza still stands just a kilometre out the Crank Road from the main street of Banagher and is currently benefitting from major conservation works carried out by Cunningham Civil and Marine under the aegis of Waterways Ireland. On the Galway side a single 24-pounder was mounted on Cromwell’s Castle and a new Martello Tower was added just a short distance away to the north. Downstream at Keelogue a magnificent battery with nine guns was erected overlooking the highly accessible ford at a cost of £7,367 16 2. Meelick Martello Tower was also erected at this time.

MEELICK MARTELLO: ACQUISITION OF LANDS 1812-14

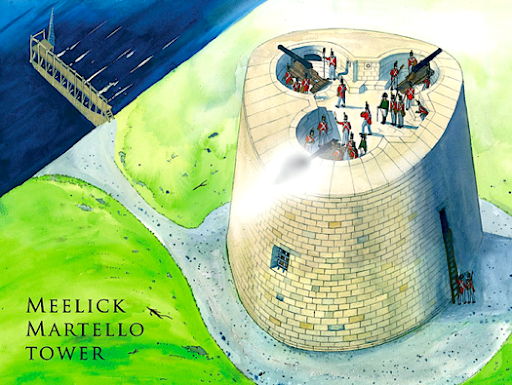

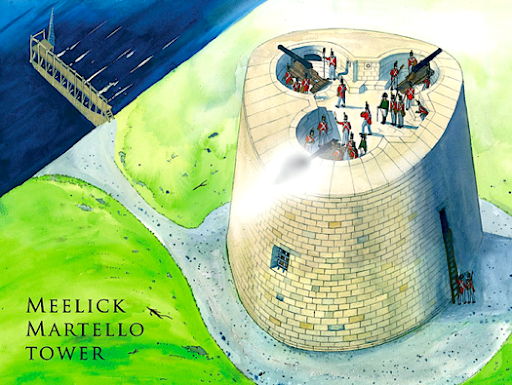

A conjectural reconstruction of Meelick Martello Tower by the artist Paul Francis, courtesy of Waterways Ireland.

Meelick Martello Tower was erected between 1811 and 1815. A detailed correspondence between the Board of Public Works (Shannon Navigation) and military authorities (Royal Engineers), over the period 1839-1856 survives in the National Archives in London, reference WO 44/719. From this we learn that following an inquisition held in Banagher on 22 June 1812 an area of land comprising 1 acre 1 rood and 16 perch in Clonahenoge, Lusmagh, was designated as the site for the tower. The Board of Ordnance’s estimate for the tower in March 1811 was £3,968 14 9 and the building was mostly finished by March 1814.

AFTER NAPOLEON

Ironically by the time the tower was finished c.1815 Napoleon had been defeated at Waterloo and consequently the threat of a French invasion of Ireland had abated. Nonetheless the fortifications continued to be garrisoned for half a century more until they were evacuated in the mid-1860s. Over the decades of peacetime that ensued many incidents occurred some of which appeared in the local newspapers.

1833 Perhaps the most embarrassing of these was in 1833. During a funeral in Meelick Churchyard four well-armed men entered one of the fortifications nearby and robbed the gunner called Williscroft obtaining £40 in cash, a gun, a case of pistols, a sword and some rounds of ammunition. More alarmingly the raiders made off with ten pounds of gunpowder. To add insult to injury the robbers ascended both the Keelogue Battery and the Meelick Martello and spiked all the guns thus rendering them useless.

1838 A newspaper account of 1838 thus described the mid-Shannon fortifications, twenty-five years after their initial construction:

They are still garrisoned by detachments from the several military stations in the adjoining towns, and by invalids of the artillery corps. The men are as well employed in this manner as in doing nothing elsewhere; or better perhaps, since it keeps their hands in for a kind of service in which it might be difficult to find other means of training them. The government, for this or for some other cause, incurs no small expense in keeping the batteries in an effective state. During the present year most of them have been refitted; and it was stated to me by a gentleman connected with the Steam Navigation Company, that its boats have recently carried nine hundred tons of wooden guncarriages from Dublin, to supply the various towers and batteries on the Shannon.

1844 In March 1844 the Tipperary Free Press recorded that an artilleryman while assisting in raising a piece of ordnance to the top of one of the Martello Towers near Banagher had his legs and ribs dreadfully mangled by a fall of the windlass at which he was engaged.

1848 Three soldiers from the 13th Light Infantry were drowned when crossing the River Shannon from the village of Meelick. The bodies of Thomas Emery and John Downes were recovered separately and following inquests by the coroner Benjamin Toy Midgley, the jury returned verdicts of ‘Casual Drowning’. Toy Midgley had been appointed coroner for the southern or Parsonstown district of King’s County just a year earlier.

1856 EVACUATION

By far the most significant event to take place in peacetime was the evacuation of the tower after a protracted dispute between the military authorities and the Board of Works. During the construction of Victoria Lock, 1841-44, the Board of Ordnance’s access road to the Martello Tower was cut off. Writing ten years later in January 1851 Colonel J. Oldfield, Colonel Staff Commanding the Royal Engineers of Ireland summed up the military’s position:

‘…..that the means of communication with the Tower from Allen’s Bridge has been cut off by the canal without any proper equivalent being secured to the Ordnance. The only passage now is by Victoria Lock, a very inefficient mode of communication with a military post.’ Not only was this route unsuitable and cumbersome but the lock keeper Mr. Brennan accused the military of trespassing as this ground had been let to him by the Board of Works. In conclusion the colonel pointedly asked what mode of communication the board were prepared to offer ‘…whether by a swivel bridge or other fit for the passage of troops and military stores’.

In spite the eminence of his office and the illustriousness of his career, including a prominent part in the Battle of Waterloo, Oldfield did not obtain satisfaction. In November 1856 the order to transfer the lands and tower at Meelick to the Board of Works was given and further ‘that the invalid gunner in charge may be instructed accordingly and that any artillery stores in the tower may be removed.’

A few weeks later, on 8 December 1856, a full return of artillery and ordnance stores removed from the tower in Meelick to the battery upstream at Keelogue was completed. This also survives in the National Archives in London and gives us a terrific insight to the intricacies of maintaining and firing handguns and cannon. Among the items listed were sponges, handspikes, case of shrapnel, fuses, musket ball cartridges, percussion caps, musket flints, wad hooks, portfire, portfire clippers, portfire sticks, pedestals, tangent scales, traversing irons, wood quoins, wood chocks, wood scotches, leather slippers, vent punches, quill tubes, barrels, wheelbarrows, tin bottles and leather cartouches. By special arrangement the heavier guns and carriages were to remain behind until the summer when the state of the ground around the tower would admit of their removal without difficulty.

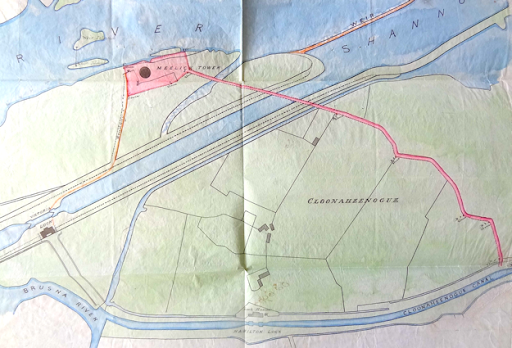

A colourful map showing the road (in pink) which gave the military access to Meelick Tower. The ordnance ground is shown in pink and the Board of Works property in green. As can be clearly seen the construction of the short canal into Victoria Lock cut through this road giving rise to the protracted dispute which resulted in the tower being evacuated by the military in 1856. Image courtesy of the National Archives, London, reference WO 44/719.

Meelick Martello Tower in 2020 after the dense overgrowth had been removed

Meelick Martello Tower is just 150 yards north-west of Victoria Lock and is often confused with the more visible Keelogue Battery, just less than a mile upstream on Incherky Island. Access to site of the tower is difficult and in periods of winter flooding it is not approachable. The Meelick Weir Walkway is now open to the public and draws a steady flow of walkers and sightseers to the area. The path from the weir to Victoria Lock passes within a hundred metres of the tower and hopefully access to the tower will improve in time to come.

WATERWAYS IRELAND

It was just a quirk of fate that in 1856 the military authorities handed over the Martello Tower to the Board of Works and that subsequent history placed it in the care of Waterways Ireland. We are most fortunate that this happened. Waterways Ireland are worthy of a well-deserved céadmíle buíochas for their endeavours locally.The magnificent restoration of Meelick Weir, the conservation work at Fort Eliza, Banagher, the ongoing maintenance of the Shannon Navigation and what will be completed in the future at Meelick Martello Tower is entirely due to them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The generosity and help of the directors and staff of the National Archives in London and the National Archives of Ireland in Dublin are greatly appreciated.